Compression is one of the most important effects when producing, giving producers complete control over the dynamics of sounds, and so helping to ensure mixes are as loud and fat as possible!

What does a Compressor do in music?

A compressor is an audio effect that makes adjustments to the level of a signal over time.

Before compressors, this would be the job of an engineer ‘riding a fader’, waiting for moments when a signal got too loud and then turning it down when that happened.

Obviously, this isn’t exactly an ideal task for an engineer, who could never be expected to respond quickly or consistently enough to ensure there were never any signal overloads, so the first analogue (hardware) compressors were born.

Over time, compressors became a standard feature on every channel of a mixing desk, as they enabled engineers to make sure levels of multiple signals, e.g. all the mics on a drum kit, guitarists, singers and so on, never exceeded a certain point during a studio recording.

Today, you can still see compressors within emulation software that replicates this kind of old hardware, be it complete mixers like that of Reason, or channel strip (compression and EQ) software of Softube or Slate Digital.

Most commonly though, you’ll find compressors being added liberally as insert or send effects in DAWs, so they can give producers complete control over levels and help them to properly fatten up the sound of their mixes.

There’s definitely no shortage of compressor plugins, each with their own blend of new technology and ‘vintage’ processing, with built-in DAW effects and 3rd-party AU/VSTs providing a wealth of options to the modern producer!.

Why do we need to compress audio?

The main reason for compressing a sound is to reduce its dynamic range, meaning the difference between its loud and quiet bits.

In some styles of music, it might be important to preserve this range, for dramatic effect, as in classical music for example, but with electronic music, which is generally noisier, it's normally more important to have consistent levels with more loudness overall.

When a sound has been compressed, or squashed as it's often called, it can then be turned up safely, without fear of its level going over the maximum clipping point on a channel (running into the red) and causing overloads.

This squashed and then boosted signal is a lot louder and so stands out in a mix a lot more than without compression.

Another reason for compressing sounds, however, can be to gel them together.

Applying very light compression to a group of sounds such as drums or all sounds on the master channel is a common way to make them sound as one, rather than as a disparate bunch of noises! So it's not all simply about making things as loud as possible.

How much compression should you apply?

The answer to this is very much dependent on the style of music you're making. If you produce very heavy dance or rock music, for example, the answer is a lot!

The reason being that this is some of the loudest music out there and, as such, it will need to be loud if it wants to compare to other tracks in the same style.

This means that most sounds (certainly the main ones) in the mix, as well as groups of sounds and all sounds together on the master channel will need to be compressed heavily to make them nice and fat.

On lighter styles of electronic music, you may get away with a bit less overall, but you'll almost certainly be applying it to all the same parts, just with slightly gentler settings.

In all styles, it's likely you'll also be using a compressor to 'duck' sounds, which is a technique also called sidechain compression, where one sound can be made to compress another.

What controls the amount of compression on a compressor?

There are two main compressor controls that determine the amount of compression:

- Threshold

- Ratio.

Threshold sets the level at which to start compressing, so any sound over that point will get turned down, and ratio defines the amount that it gets turned down.

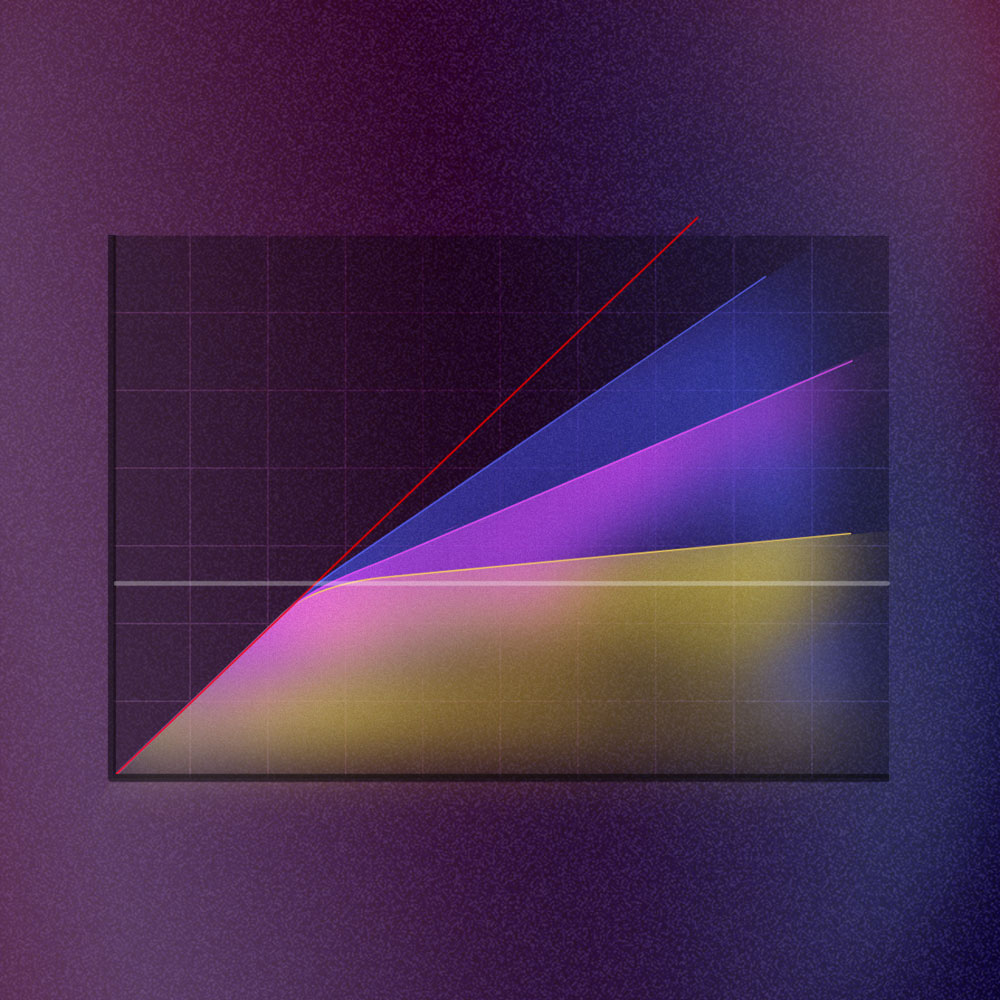

These two parameters create the compressor curve, as shown in the following diagram:

The speed of the compressor also has a big role to play in the amount of compression, as a slow compressor won't result in nearly as much compression as a fast one, particularly on a rapid signal, like a drum beat for instance.

The two parameters that define the speed are Attack and Release, which set how quickly the compressor starts and stops compressing, respectively.

The type of compressor you are using, or more likely the software emulation you have, will also be a big factor here, as different types of compressor circuitry have their own individual responses and characteristics.

Also, controls such as the compressor knee, and whether the device uses Peak or RMS detection will have an effect on this.

What is Sidechain Compression?

The sidechain of a compressor is its detection circuit, meaning the part of the device that the compressor responds to when compressing.

As default, this contains the signal that's being compressed, so the compressor responds to the signal its compressing, but another option is to route a different signal into the compressor sidechain, so the compressor can react to that instead.

A classic example is routing a kick drum into a bass's compressor sidechain, so that the bass compresses when the kick hits, creating the ducking or pumping effect that's heard in dance music all over!

Check out this example of classic sidechain compression, demonstrated by Senior Tutor Rob Jones, in the excerpt from his recent Compression Fundamentals Course: